- John Muscat

|

| Model of Sydney's proposed North Western Expressway - it was never built |

If Twitter is any indication, the co-existence of freeways and CBDs or downtowns is a hot issue. Urban planning Twitter is full of laments, mostly from Americans, about the impact of freeways built since the 1950s on inner-city precincts. Many claim they were created with racist intentions, to destroy minority neighbourhoods or stifle their economic development. US Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg says “there is racism physically built” into some highways. It seems more likely the controversy relates to gentrification of the urban core and a new focus on lifestyle amenity over economic efficiency in transport infrastructure. In the United States, where processes of inner-urban gentrification are a more recent development, the emphasis is on tearing down existing downtown freeways and blocking new ones. This has developed into a crusade and the tone of advocacy is militant. Accusations of racism and environmental degradation are thrown around indiscriminately. “Urban freeway removal” is something of a movement amongst progressive urban activists across American metro areas.

In Australia the history is in some ways different. Like the US, Australia saw a post-war trend of industrial dispersion from the core and the emergence of new industrial suburbs on the periphery. Some American writers are apt to label this out migration “white flight”. But the same phenomenon occurred in more racially homogenous Australian cities. The real causes have to do with technological developments in manufacturing and transportation, like advanced assembly-line automation − more space extensive plant layouts − and mass adoption of commercial and passenger motor vehicles together with containerisation of freight shipping. These trends were duly noted by urban analysts of the era. One classic account is Anatomy of a Metropolis by Edgar M Hoover and Raymond Vernon, published in 1962 for the New York Metropolitan Region Study. Hoover and Vernon observed that

[o]ne of the

most universal changes in factory processes over the past 30 or 40 years has

been the widespread introduction of continuous-material-flow systems and of

automatic controls in processing … the disadvantages of operating on a

less-than-ideal structure have grown rapidly. Today, the common practice in

many lines of manufacture is to find a site which imposes the least possible

restraints on the shape of the structure. The shape and size of city block

grids, therefore have become a powerful restraint on factory location …

“Motor transport had a double-barreled impact in

pushing industry out of the [inner] cities of the Region”, they write. “Not

only did it offer a new freedom to the manufacturer in selecting a site but it

accentuated the disadvantages of the obsolescent street layout of the [inner] cities”.

The “search for space”, as Hoover and Vernon call it, would “inevitably move

outward to exploit the new locational freedom which the truck, the airplane,

and piggy-back freight have afforded”. Development of these spatial

arrangements into a functional metropolitan system called for more efficient

two-way transportation links between core and periphery: “high-speed highways

which will converge on the Core and Inner Ring are bringing an obvious change

in … Outer Ring areas, one which is beginning to link them more clearly to the

Region”. The ramifications flowed in both directions:

… the high-speed

highway will also affect the location of middle-income housing. For occupants

of this kind of housing in the Outer Ring, ties to [downtown] are not nearly so

important as ties to the plants and businesses of the Inner Ring. The highways

are important … because they bring large new tracts of undeveloped land into

the market for mass builders of moderately priced colonies.

|

| James Kirby machine tool plant, Milperra, western Sydney, early 1970s |

Similar trends emerged in other industrialised countries. They were acknowledged with much foresight in the NSW Government’s County of Cumberland Planning Scheme of 1948, which provided for new industrial land in places on Sydney’s then western periphery like Bankstown and a radial expressway network. These particular roads never materialised, but the vision of an integrated core-periphery metropolis adumbrated by the likes of Hoover and Vernon shaped the received model of urban and transportation planners until the mid-1970s. At around that time the dual processes of deindustrialisation and gentrification rolled over the core more or less simultaneously, unlike in the United States. Whereas American anti-highway activists are having to fight a rearguard action to dismantle inner-city freeways – “about 18 U.S. highways have been removed in some form since the late 1970s, with a significant spike in the past five years” – Sydney’s counterparts had an opportunity to launch a pre-emptive strike.

In line with the integrated core-periphery model, NSW’s Department of Main Roads proposed a project in the late 1960s known as North Western Expressway, linking Sydney CBD to its north-western suburbs and ultimately the Sydney-Newcastle Freeway to Newcastle. The route traversed inner-west neighbourhoods including Glebe, Annandale, Lilyfield and Rozelle, former working-class areas which by the 1970s were at an advanced stage of gentrification. For the new professional inhabitants working in fields like “public administration, academia, media, advertising, architecture, design, and the arts, these charming 19th century streetscapes lined with workingmen’s cottages and terraces, close to the city centre’s office jobs and rich cultural amenities, were ideal ‘lifestyle’ locations”. This youthful cohort had the qualifications and political connections to wage a potent campaign against this encroachment on their turf, which ultimately proved successful. On regaining office at the 1977 NSW state election, Labor scrapped the project.That was the death knell of motorways crossing inner Sydney for decades and the consequences are plain to see. If post-war planners were seized by a vision of metropolitan integration, present day reality is akin to a condition of disintegration. Loss of close socio-economic diversity in the core was not relieved by rapid, far-reaching transport connections with the periphery. Central Sydney turned its back on Greater Sydney. Imitating their precursors who stopped North Western Expressway, a new wave of political and municipal leaders shrugged off broader regional priorities and hurried to refashion the CBD in their own image. Raymond E Murphy, author of the classic textbook The Central Business District: A Study in Urban Geography (1971), considered the CBD an outward formation, drawing “its business from the whole urban area and from all … classes of people”. On this definition Sydney isn’t so much a CBD anymore as an exclusive playground for its high-end workers and growing number of well-heeled residents.

|

| Classic CBD - Sydney, 1960s, bustling and proletarian |

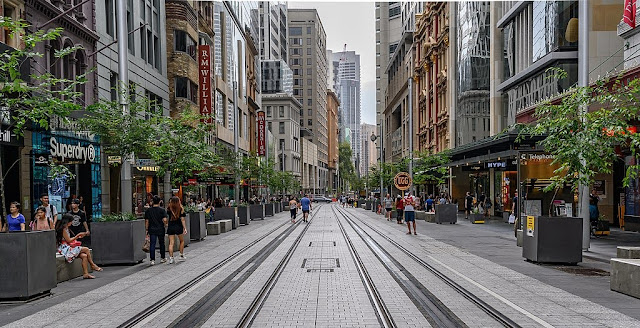

One visible manifestation of this is a progressing ‘luxurisation’ of the streetscape. Today’s relaxed ambience – even before the pandemic − and upscale establishments stand in contrast to the bustling city of decades ago with its traffic and distinct proletarian aspect. Traditional rows of discount stores and intermittent warehouses have in stretches been displaced by large block-like glass and concrete facades brandishing global brands, above hip boutiques, eateries and banks of street furniture. This amenity grab was achieved by furtive step-by-step obstructions to motor vehicles, still the largest dimension of modern transportation. As CBD entry points are aligned to a handful of public transport corridors, withdrawal of parking spaces and a creeping cordon of pedestrianised streets and plazas, light-rail lines, criss-crossing bike lanes and falling speed limits deter driving and help keep most of Sydney’s population away in their distant abodes. If current trends continue the CBD is destined to become a gated resort-style campus for the Western Pacific Region’s high-flying globetrotters.

|

| Post-CBD - Sydney, 2021, upscale and exclusive |

There is no widely accepted term to describe this new urban phenomenon in central Sydney and other world cities, but ‘post-CBD’ is as good as any.

This article was republished in On Line Opinion, Australia's e-journal of social and political debate.

The New City main site is here: www.thenewcityjournal.net

Comments

Post a Comment